Fire Detection Inside Enclosures: Why Cabinet-Level Fires Require a Fundamentally Different Detection Logic

Introduction: Why Fire Detection Changes at the Enclosure Level

Fire detection is often discussed as though it were a universal problem with a universal solution. In practice, detection logic is inseparable from the physical environment in which a fire develops. Nowhere is this more apparent than inside electrical cabinets, industrial enclosures, and equipment housings, where fires originate, grow, and interact with their surroundings in ways that differ fundamentally from fires in open rooms.

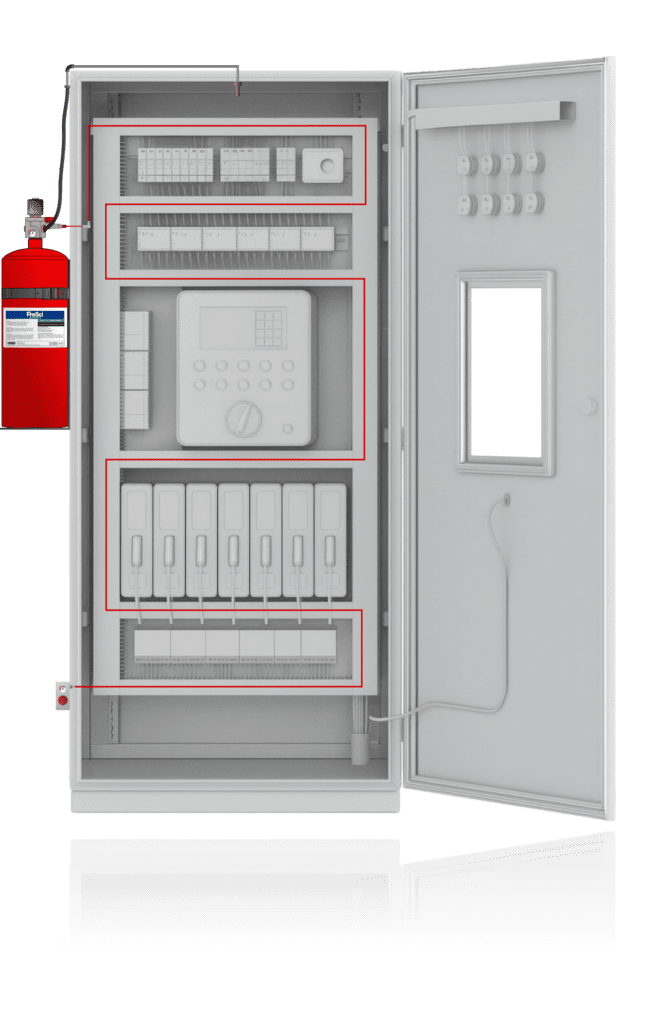

A large percentage of electrical and equipment-related fires begin inside enclosures—control panels, switchgear cabinets, server racks, battery housings, and machine tool compartments. These fires typically originate from overheated conductors, failing insulation, loose connections, or component faults. In their earliest stages, they are spatially confined, thermally concentrated, and largely invisible to the surrounding room. As a result, detection systems designed for open volumes are inherently delayed when applied to enclosure-origin fires.

This reality has led to the emergence of enclosure-level fire detection as a distinct discipline within fire protection engineering. Detecting a fire inside an enclosure is not simply a matter of placing a detector “closer.” It requires a different detection logic altogether—one grounded in confinement physics, localized heat behavior, restricted airflow, and delayed smoke migration. Understanding these differences is essential for designing suppression systems that intervene early enough to prevent escalation, equipment loss, or secondary fires.

Fundamental Differences Between Room Fires and Enclosure Fires

Room-level fire detection is built around assumptions that do not hold true inside enclosures. Open rooms are characterized by large air volumes, relatively uniform ambient conditions, and predictable smoke and heat movement patterns. Detection thresholds for room detectors are calibrated to avoid nuisance alarms while reliably identifying fires that have grown large enough to threaten occupants or structures.

Enclosures, by contrast, are confined volumes with radically different thermal and fluid dynamics. The ratio of fire size to volume is much higher, meaning that temperature rises occur rapidly and locally. Heat does not dissipate freely but accumulates near the ignition source. Smoke does not immediately rise to a ceiling; it remains trapped, diluted, or redirected by internal geometry.

Because of this, detection thresholds appropriate for rooms are often mismatched to enclosure conditions. By the time a cabinet fire produces enough heat or smoke to trigger a ceiling-mounted detector, the fire may have already caused catastrophic damage inside the enclosure. Detection logic that works at the room scale is therefore temporally misaligned with enclosure fire development.

Fire Growth and Heat Accumulation Inside Enclosures

Heat behavior is the most immediate differentiator between enclosure fires and room fires. Inside an enclosure, heat released from a fault has nowhere to go. Metal walls reflect radiant energy, internal components absorb and re-radiate heat, and convection is constrained by the enclosure’s geometry.

As a result, localized temperatures near the ignition source rise quickly, often reaching ignition or decomposition thresholds for nearby materials long before the enclosure exterior exhibits noticeable temperature changes. Thermal stratification can occur even within small volumes, creating extreme hot spots at cable terminations, bus bars, or power supplies while adjacent areas remain relatively cool.

This rapid, localized heat buildup explains why enclosure fires often escalate internally without external warning. From the perspective of the surrounding room, the enclosure may appear unchanged until the fire breaches containment or triggers secondary effects. Effective detection must therefore operate within the enclosure, responding to thermal conditions at or near the point of ignition rather than relying on averaged room conditions.

Smoke Behavior in Enclosed Spaces

Smoke behavior inside enclosures further complicates detection. In open rooms, smoke rises, accumulates at the ceiling, and spreads laterally, eventually intersecting smoke detectors. Inside enclosures, smoke movement is constrained, fragmented, and often delayed in reaching the external environment.

Smoke particles generated inside a cabinet may circulate internally, adhere to surfaces, or exit through small ventilation openings only after significant accumulation. In some cases, smoke is actively diluted by cooling fans before it can escape the enclosure. In others, it remains trapped until a door seam or cable entry allows gradual leakage.

This behavior explains why room-level smoke detectors frequently fail to provide early warning for cabinet fires. By the time smoke reaches the ceiling in sufficient concentration, the enclosure fire has often progressed beyond the incipient stage. Detection logic that assumes prompt smoke migration is therefore unsuitable for enclosure-origin fires.

Airflow, Ventilation, and Pressure Effects

Airflow inside enclosures introduces additional complexity. Many electrical and electronic cabinets rely on forced ventilation to manage operational heat loads. Fans draw air in, circulate it across components, and exhaust it through vents or filters. While this airflow is essential for normal operation, it disrupts conventional detection assumptions.

Forced airflow can delay detection by cooling hot components, dispersing smoke, or preventing heat accumulation at predictable locations. Pressure differentials may cause smoke to exit preferentially through specific paths, bypassing detectors entirely. In some cases, airflow masks early fire signatures until a fan fails or the fire overwhelms the cooling system.

Positive-pressure enclosures may resist smoke ingress into detection zones, while negative-pressure designs may continuously draw smoke away from detection points. These dynamics reinforce the need for detection logic that accounts for airflow effects rather than assuming static conditions.

Why Room-Level Detection Is Insufficient for Enclosure Fires

The cumulative effect of confined heat, delayed smoke migration, and distorted airflow is detection latency. Room-level detectors are simply not positioned or calibrated to respond during the critical early phase of enclosure fires. This latency has tangible consequences.

Delayed detection allows fires to escalate internally, increasing damage severity and the likelihood of secondary ignition. It also undermines suppression effectiveness. Many suppression systems, particularly micro-enclosure systems, rely on early intervention to extinguish fires before they involve multiple fuel sources or breach containment.

Enclosure-level detection exists precisely to address this gap. It is not a redundant layer but a necessary one, designed to detect fires where they start rather than where their byproducts eventually appear.

Detection Logic Inside Enclosures

Detection inside enclosures is fundamentally proximity-based rather than area-based. Instead of monitoring an entire room for generalized fire signatures, enclosure detection focuses on sensing localized conditions indicative of ignition within a confined volume.

This logic favors detection methods that operate continuously along potential ignition paths or that respond directly to thermal exposure at the component level. The emphasis shifts from detecting “a fire somewhere in the room” to detecting “abnormal conditions at the source.”

From a design perspective, this reframing is critical. Detection becomes a system-level decision tied to enclosure geometry, internal layout, and risk concentration, rather than a simple choice of detector type.

Enclosure-Level Detection Modalities (Conceptual Only)

At a conceptual level, enclosure detection can be broadly categorized by the physical phenomenon it monitors. Heat-based approaches respond directly to thermal exposure, while smoke-based approaches respond to combustion byproducts. Mechanical detection methods exist alongside electronic sensing, offering alternatives where power independence or environmental robustness is required.

The suitability of any detection modality depends on how well it aligns with enclosure fire dynamics. In many cases, detection logic is defined less by the sensor itself and more by how and where it interacts with the enclosure environment. This reinforces the principle that detection is an architectural problem, not a component selection exercise.

Relationship Between Detection and Suppression Timing

Detection speed directly governs suppression effectiveness. In micro fire suppression systems, the window between ignition and escalation is narrow. Suppression systems are most effective when activated during the incipient phase, before heat release rates increase and multiple fuels become involved.

Delayed detection compresses this window or eliminates it entirely. Even the most capable suppression system cannot compensate for detection that occurs after critical thresholds have been crossed. For this reason, detection and suppression must be designed as an integrated sequence rather than independent subsystems.

Enclosure-level detection ensures that suppression systems are triggered based on conditions at the source, maximizing the likelihood of rapid extinguishment and minimizing collateral damage.

Common Detection Design Failures in Enclosures

Many enclosure detection failures stem from applying room-level assumptions to cabinet environments. Common issues include relying on ambient temperature measurements rather than localized heat exposure, ignoring airflow patterns that dilute or redirect detection signals, and treating detection as a secondary consideration after suppression selection.

Another frequent failure is assuming that enclosure detection is unnecessary if room detection exists. This assumption overlooks the temporal mismatch between enclosure fire development and room detector response. Effective detection design begins with acknowledging that enclosures are distinct fire environments requiring tailored logic.

Relationship to Other System-Level Topics

Fire detection inside enclosures does not exist in isolation. Detection logic directly influences activation mechanisms, suppression architecture, and system reliability. Detection tubing design builds upon the principles discussed here, translating thermal exposure into mechanical or pneumatic response. Activation logic determines how detection signals initiate suppression. Enclosure fire dynamics explain why early detection is so critical, while architectural choices such as Direct and Indirect Low-Pressure systems define how detection integrates with discharge behavior.

This page provides the foundation upon which those topics are built, establishing the physical and logical context for more detailed discussions.

Closing Perspective

Fire detection inside enclosures is a first-principles problem rooted in physics, not a scaled-down version of room detection. Confined volumes behave differently, fires develop differently, and detection must respond accordingly. By recognizing enclosure detection as its own discipline, engineers can design systems that detect fires where they begin, intervene when it matters most, and prevent small faults from becoming catastrophic events.

Early detection defines system success. In enclosure fire protection, understanding detection logic is not optional, it is foundational.