Clean Agent Fire Suppression Explained: Principles, Fire Interaction, and Enclosure-Level Design Logic

Orbis Fire Suppression Guide | 7 min read

Introduction: Why “Agent Logic” Matters in Fire Suppression

In the intricate domain of fire protection engineering, the effectiveness of a suppression system is fundamentally dictated by the inherent logic of the extinguishing agent itself—how it interacts with combustion, dissipates energy, and behaves within a defined volume. This understanding transcends mere product specifications; it delves into the core principles of fire science and the architectural design required for optimal performance. Clean agents represent a specialized category of extinguishing mediums, developed as a precise response to the unique challenges posed by fires within critical micro-enclosures, such as electrical cabinets, server racks, and high-value industrial equipment.

The selection of a fire suppression agent is not an isolated decision. It must be a logical extension of architectural choices, intimately tied to the system’s geometry (e.g., Direct Low-Pressure vs. Indirect Low-Pressure systems) and the specific characteristics of the protected enclosure. A clean agent, by its very nature, demands particular environmental conditions to perform optimally. This article aims to elucidate the underlying principles of clean agent suppression, exploring their conceptual definition, their interaction with fire, and the critical enclosure-level design considerations that govern their effective application. It seeks to provide a foundational understanding for engineers and designers, clarifying the “why” and “how” of clean agent technology, rather than merely cataloging specific products.

What Defines a Clean Agent (Conceptually, Not Commercially)

From an engineering and fire science perspective, a “clean agent” is characterized by its physical and chemical properties that allow it to extinguish a fire without leaving behind corrosive, abrasive, or electrically conductive residue. This definition distinguishes clean agents sharply from conventional suppressants like water, which can cause extensive damage to electronics; foam, which leaves a significant residue; or dry chemical powders, known for their cleanup challenges and potential for equipment abrasion.

The conceptual hallmarks of clean agents include:

- Gaseous or Vaporizing Liquid State: At the point of discharge, clean agents are either gases or rapidly vaporize into gases. This allows them to quickly and uniformly disperse throughout an enclosed volume, penetrating complex equipment geometries.

- Non-Conductivity: They do not conduct electricity, making them safe for use in energized electrical and electronic environments without risk of short circuits or further damage.

- Non-Corrosive and Non-Abrasive: Upon discharge, they do not react adversely with sensitive materials, preserving the integrity of circuit boards, delicate machinery, and data storage devices.

- Minimal Post-Discharge Residue: The defining characteristic is the absence of residue, which drastically reduces downtime and cleanup costs after a fire event. This facilitates rapid operational recovery, a critical factor in mission-critical applications.

This classification is based purely on the functional behavior of the agent in a fire scenario and its subsequent impact on the protected environment, detached from any specific regulatory or commercial appellation.

Fire Science Fundamentals: How Clean Agents Extinguish Fire

Clean agents primarily extinguish fires through two fundamental mechanisms, often working in concert: heat absorption and the interruption of the chemical chain reaction of combustion. Oxygen displacement can also play a role, particularly with certain agents like CO₂, but it is generally a secondary mechanism for the commonly applied chemical clean agents.

- Heat Absorption (Cooling): Many clean agents, particularly fluorinated ketones (e.g., FK-5-1-12) and some hydrofluorocarbons (e.g., HFC-227ea), absorb significant amounts of heat energy from the flame. This process lowers the temperature of the combustion zone below the point where sustained combustion can occur. As the agent vaporizes or expands, it draws thermal energy from the fire and its surroundings, effectively “cooling” the flame.

- Free-Radical Interruption (Chemical Interference): The most potent clean agents operate by physically interfering with the chemical chain reaction of combustion. Fires are sustained by a self-perpetuating cycle of free radicals (highly reactive atoms or molecules) that react with fuel and oxygen. When discharged, clean agents break down in the presence of heat, releasing inert molecules or atoms that scavenge these free radicals. By neutralizing the free radicals, they interrupt the propagation of the fire at a molecular level, stopping combustion before it can continue.

It is crucial to understand that clean agents are most effective in enclosed volumes. This is because their ability to absorb heat or interrupt reactions relies on achieving and maintaining a specific concentration within the protected space. In an open environment, the agent quickly dissipates, rendering it ineffective. Their design logic is therefore predicated on establishing a transient atmosphere hostile to combustion, rapidly overwhelming the fire’s ability to sustain itself. This demands a contained environment where the agent can achieve and hold its design concentration for a sufficient “soak time.”

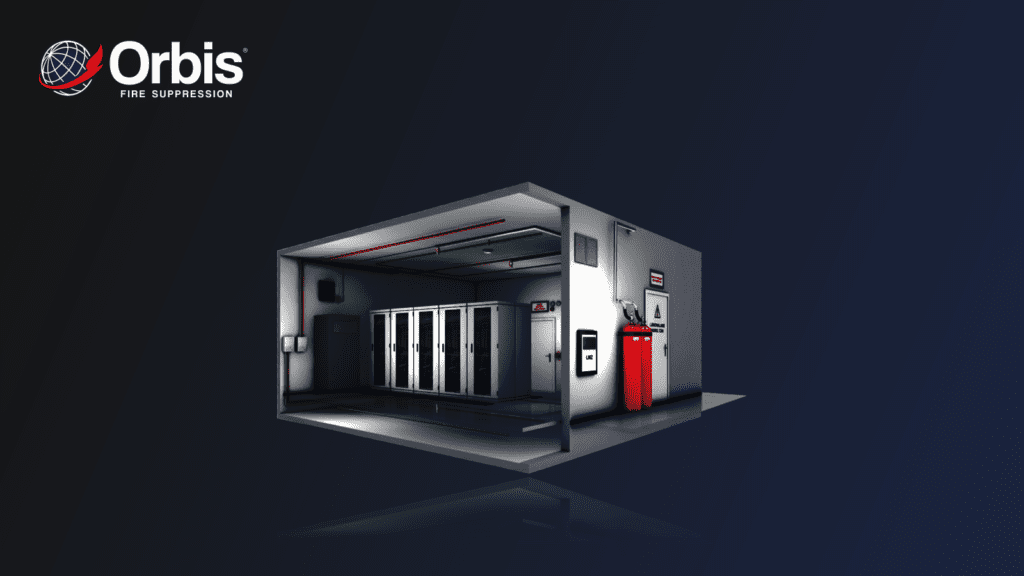

Clean Agents in Micro-Enclosure Fire Suppression

Micro-enclosure fire suppression, targeting fires within volumes typically ranging from a few liters to several cubic meters (e.g., electrical cabinets, control panels, small data racks), represents a quintessential application for clean agents. The attributes of these agents align perfectly with the unique fire dynamics and risk profiles inherent to such confined spaces.

Within a micro-enclosure, fires often begin as small electrical faults—overheated components, short circuits, or insulation failures. These fires typically involve energized equipment, sensitive electronics, and often limited access for manual intervention. Here, clean agents excel for several reasons:

- Rapid Dispersion in Confined Spaces: The gaseous or rapidly vaporizing nature of clean agents allows for swift and uniform distribution throughout complex internal geometries, circumventing obstructions like circuit boards, wiring bundles, and power supplies that would impede water or powder.

- Interaction with Enclosure Airflow and Heat Rise: Micro-enclosures, especially those with internal fans, can develop localized hot spots and complex airflow patterns. Clean agents, when discharged as a total flood, can rapidly dilute these hot zones and extinguish fires before they escalate, often overcoming mild internal airflow. The speed of discharge is critical; a rapid discharge ensures the agent reaches fire-extinguishing concentration before the fire can grow or spread significantly.

- Minimizing Collateral Damage: The primary value proposition in micro-enclosures is the preservation of the asset itself. Clean agents achieve this by extinguishing the fire without leaving residue, allowing for immediate assessment and often rapid recommissioning of the equipment, rather than requiring extensive cleanup or replacement. This speed of recovery is often more valuable than the cost of the agent itself.

Relationship Between Agent Behavior and System Architecture

The fundamental behavior of clean agents—their need for concentration, their gaseous nature, and their extinguishing mechanisms—is inextricably linked to the chosen system architecture, whether Direct Low-Pressure (DLP) or Indirect Low-Pressure (ILP). The agent’s characteristics inform which architecture is most appropriate for a given fire scenario.

- Clean Agents in Direct Low-Pressure (DLP) Systems: In a DLP system, the clean agent is discharged directly through a rupture in the detection tubing. This creates a highly localized, high-velocity stream of agent. This localized discharge logic aligns well with clean agents when the protected volume is small and compact, and the risk points are clearly defined. The agent, often stored as a liquid under pressure (like FK-5-1-12), rapidly flashes to gas upon discharge, attempting to fill the immediate area of the rupture. While primarily a “point-of-ignition” attack, the inherent expansion of the clean agent helps it permeate the very localized hot zone. The success here relies on the fire being small and the enclosure being tight enough for the localized agent cloud to achieve extinguishing concentration around the fire’s origin.

- Clean Agents in Indirect Low-Pressure (ILP) Systems: ILP systems, by contrast, use discrete nozzles to distribute the clean agent, achieving a total flooding effect. This architectural approach is inherently better suited for leveraging the full potential of clean agents in larger or more complex enclosures. With ILP, the clean agent is designed to achieve a uniform, calculated concentration throughout the entire protected volume. This ensures that even fires hidden behind obstructions or in areas of varied airflow receive adequate agent. The total flooding capability of ILP ensures that the clean agent’s chemical and physical extinguishing properties are maximized across the entire risk zone, making it the preferred architecture for scenarios where maintaining a precise design concentration throughout the volume is paramount for complete extinguishment and re-ignition prevention.

The choice of agent behavior (localized discharge vs. total flooding) is not isolated. A system designed for total flooding with a clean agent must consider factors such as enclosure integrity, discharge time, and agent hold time—all of which are optimized through an ILP architecture.

Enclosure Characteristics That Favor Clean Agents

The successful application of clean agents is highly dependent on the inherent characteristics of the protected enclosure. Certain enclosure attributes create an optimal environment for clean agent performance, while others present significant challenges.

Enclosure Characteristics Favoring Clean Agents:

- Sealing and Integrity: Clean agents are most effective in enclosures that can maintain a minimum level of integrity. A well-sealed enclosure is crucial for retaining the design concentration of the gaseous agent for the required “hold time”—the duration necessary to ensure complete extinguishment and prevent re-ignition. Significant leakage points (e.g., large cable openings, unsealed ventilation gaps) can rapidly dissipate the agent, rendering it ineffective.

- Defined Volume: The protected volume must be clearly defined and calculable. This allows engineers to accurately determine the quantity of agent required to achieve the design concentration.

- Low to Moderate Airflow: While clean agents can overcome some internal airflow from cooling fans, excessive, continuous, or rapidly changing airflow can dilute the agent and make it challenging to maintain the extinguishing concentration.

- Internal Obstructions (Complex Geometry): Unlike water or foam, the gaseous nature of clean agents allows them to penetrate complex internal structures within cabinets, such as dense wiring, circuit boards, and numerous components, ensuring that the agent reaches the seat of the fire irrespective of its precise location within the labyrinthine space.

Enclosure Characteristics That Present Challenges for Clean Agents:

- High Leakage or Openings: Enclosures that cannot be reasonably sealed or have large, permanent openings (e.g., open-front server racks, un-partitioned industrial machinery) are generally poor candidates for clean agents. The agent will escape before it can achieve or maintain concentration.

- Persistent High Temperatures or Re-ignition Sources: While clean agents extinguish flames, they may struggle with deeply seated fires or materials that can re-ignite from smoldering heat sources after the agent has dissipated. The enclosure must cool sufficiently during and after discharge.

- High-Velocity Airflow: Industrial processes with very high continuous airflow can rapidly strip the agent away, making it difficult to achieve and hold a sustained concentration.

The decision to use a clean agent is a design tradeoff. It requires a realistic assessment of the enclosure’s ability to contain the agent and the nature of the potential fire.

Safety, Occupancy, and Operational Considerations

A significant advantage of clean agents, particularly in the micro-enclosure context, lies in their safety profile regarding human exposure and their minimal impact on post-discharge operations. This is a critical factor for equipment located in occupied technical spaces, control rooms, or data centers.

- Human Exposure Profile: Most modern clean agents are designed with a wide margin of safety between their extinguishing concentration and their “no observable adverse effect level” (NOAEL) for human exposure. This means that, in properly designed systems, personnel who may be in the vicinity of an enclosure discharge are unlikely to suffer acute toxic effects. While evacuation is always recommended during any fire event, and an alarm will always precede discharge, the inherent low toxicity of these agents allows for their application in areas where human presence is a constant. It’s important to distinguish this from CO₂, which, while also a clean agent, displaces oxygen to a degree that makes it immediately hazardous to life in concentrations required for fire suppression.

- Operational Recovery: The residue-free nature of clean agents dramatically minimizes business interruption. Following a discharge, there are no chemicals to clean up, no equipment to dry out, and no corrosive damage to mitigate. This allows for an immediate assessment of the fire damage (if any) and a rapid return to service for the protected equipment, provided the fire was successfully extinguished and the cause rectified. This near-zero downtime is often the primary driver for selecting clean agents over traditional suppression methods in critical infrastructure.

- Ventilation and Post-Discharge Scavenging: After an activation, the gaseous agent must be safely vented from the enclosure. This typically involves the activation of exhaust fans (either existing or dedicated) to clear the atmosphere and restore normal breathing conditions, if the area is occupied. The speed of this scavenging depends on the agent, the enclosure volume, and the ventilation rates.

The operational resilience offered by clean agents directly contributes to the overall reliability and continuity of mission-critical systems.

8. Limitations and Failure Scenarios

While highly effective in their intended applications, clean agents, like any engineering solution, possess inherent limitations and are susceptible to specific failure scenarios if misapplied or improperly maintained. Understanding these boundaries is critical for responsible design.

- High Leakage: The most significant limitation of clean agents is their absolute reliance on enclosure integrity. A system designed for a sealed cabinet will fail if the cabinet is left open, or if new, unsealed penetrations are introduced. The agent will simply escape, preventing the achievement of the required extinguishing concentration.

- Deep-Seated or Smoldering Fires: Clean agents primarily extinguish flaming combustion. While they can cool a fire, they may struggle with deeply seated smoldering fires (e.g., certain types of compacted paper, coal, or insulation materials) that retain significant residual heat. If the smoldering source reignites after the agent has dissipated, the system’s effectiveness is compromised.

- Continuous Heat Sources: Fires fueled by a continuous, high-temperature heat source (e.g., an arc furnace or a continuous chemical reaction) may overwhelm the cooling and chemical interference mechanisms of clean agents. The agent might extinguish the flame, but the persistent heat source could rapidly re-ignite the fuel once the agent disperses.

- Incompatible Materials: While generally non-reactive, rare instances of specific material incompatibility may exist, warranting careful review.

- Improper Design or Installation: Undersized systems, incorrect nozzle placement (in ILP), or tubing misplacement (in DLP) can all lead to failure, regardless of the agent’s inherent properties. This underscores the need for meticulous engineering.

These limitations are not inherent flaws in the clean agents themselves but rather emphasize the importance of matching the agent’s capabilities to the specific fire hazard and the architectural characteristics of the protected enclosure.

Clean Agent Suppression vs Other Suppression Approaches

To truly appreciate the “logic” of clean agents, it is helpful to conceptually contrast them with other common fire suppression approaches, focusing on their behavior and consequential impact.

- Vs. Water-Based Systems (Sprinklers/Mist): Water primarily extinguishes by cooling and smothering. While highly effective for general building fires, its electrical conductivity, potential for water damage, and inability to penetrate complex micro-enclosure geometries make it unsuitable for sensitive equipment. Clean agents offer targeted, residue-free protection where water would cause more damage than the fire itself.

- Vs. Dry Chemical Systems: Dry chemical agents (e.g., ABC powder) extinguish by chemical interruption and smothering. They are highly effective but leave behind a corrosive, abrasive, and difficult-to-clean residue that can destroy sensitive electronics and machinery. Clean agents provide equivalent extinguishing power without this severe collateral damage, making them the preferred choice for high-value assets.

- Vs. CO₂ Systems: Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) is also a clean, gaseous agent that extinguishes primarily by oxygen displacement and some cooling. It is highly effective and leaves no residue. However, CO₂ concentrations required for fire suppression are immediately hazardous to human life, necessitating strict safety protocols, pre-discharge alarms, and often, unoccupied space applications. Modern chemical clean agents typically offer similar extinguishing performance with a much wider safety margin for human exposure, making them suitable for occupied enclosures or areas adjacent to human activity.

This conceptual comparison illustrates that clean agents fill a critical niche: providing rapid, effective, residue-free suppression in environments where collateral damage and downtime must be minimized, often with a favorable safety profile for personnel.

How Clean Agent Logic Fits Into a Layered Fire Protection Strategy

Clean agent fire suppression, particularly in micro-enclosures, should never be viewed as a standalone, monolithic solution. Instead, it functions as a crucial, specialized layer within a comprehensive, multi-tiered fire protection strategy. Its logic is to provide immediate, localized, and non-damaging intervention at the nascent stage of a fire, preventing escalation.

- Integration with Detection: Clean agents rely entirely on prompt and accurate detection. Whether initiated by a heat-sensitive tube (DLP/ILP), smoke detectors, or aspirated sampling systems, the agent’s effectiveness is directly proportional to the speed and reliability of the detection mechanism. The detection system provides the “eyes” and “brains” that tell the clean agent “when” and “where” to act.

- Synergy with Enclosure Design: The success of clean agents is intrinsically tied to the physical design of the protected enclosure. A well-designed cabinet that minimizes leakage, separates electrical components from potential fuel sources, and manages internal airflow effectively creates an optimal environment for clean agent performance.

- Relationship to Building-Level Protection: Micro-enclosure clean agent systems act as a “first line of defense,” mitigating fires at their source before they can grow large enough to trigger building-level systems like sprinklers. This preserves the main facility from unnecessary activation, water damage, and operational disruption. It’s a proactive, preventive layer that complements, rather than replaces, larger building fire safety measures.

The overarching logic is to apply the right tool at the right scale: clean agents for the precision strike at the heart of an asset, working in concert with broader facility protection measures.

Relationship to Other Fire Suppression Topics

This exploration of clean agent principles provides a foundational understanding. For a complete and actionable grasp of micro-enclosure fire suppression, this pillar article serves as a gateway to several deeper, more specific topics, each of which elaborates on critical design and application considerations:

- FK-5-1-12 Agent Characteristics: A detailed examination of this specific fluorinated ketone’s physical properties, extinguishing mechanisms, safety profile, and application guidelines.

- HFC-227ea Agent Characteristics: An in-depth look at the properties, performance, and specific use cases for this widely adopted hydrofluorocarbon agent.

- CO₂ in Enclosure Suppression: A focused discussion on the unique properties and application considerations of CO₂ as a clean agent, particularly concerning its oxygen displacement mechanism and life safety protocols.

- DLP vs ILP Architecture: A comprehensive comparison of Direct Low-Pressure and Indirect Low-Pressure system designs, elucidating their operational differences and suitability for various enclosure types.

- Detection Tubing and Discharge Behavior: An analysis of the engineering behind heat-sensitive detection tubing, its rupture characteristics, and how agent discharge patterns are influenced by system architecture.

These specialized topics build upon the architectural and agent logic established here, providing the granular detail necessary for comprehensive system design and implementation.

Closing Perspective

The effective deployment of clean agent fire suppression is a testament to thoughtful engineering, not simply the deployment of a specific chemical. It is about understanding the subtle dance between fire science and enclosure dynamics, applying agents whose fundamental logic aligns with the precise demands of protecting sensitive, mission-critical assets. By embracing a design-first perspective, recognizing that the “why” and “how” of an agent’s function dictate its application, engineers can leverage clean agents as powerful, precise tools to safeguard invaluable equipment and ensure operational continuity. They are not a universal panacea, but rather a highly specialized, indispensable component of a modern, layered fire protection strategy.